Looking for Hope for Vietnam’s Ungulates…in Idaho

By Kristin Arakawa

When Minh Nguyen, a student at Science University in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, first saw a Southern Red Muntjac in the wild in Lang Biang Biosphere Reserve, she was in awe.

“It was so beautiful,” Nguyen says. “The muntjac was just there eating grass in front of me. It was so amazing to see the animal in the wild, rather than in captivity. Today, that is the memory that drives my work to protect the Large-Antlered Muntjac, which is much less common than the Red Muntjac that I saw in the park that day.”

For most people, dedicating time and effort to protecting a species they’ve never seen in the wild would be a difficult and maybe even dispiriting task, especially if they hadn’t seen it because the species was approaching extinction. But the Large-antlered Muntjac is one of two Critically Endangered species (the other is the Saola) Nguyen has never seen, but is passionately helping to save.

That passion is, in part, how Nguyen found herself on the other side of the world in January, pinning down a Mule Deer in Idaho while a researcher placed a telemetry collar on the animal. Her visit wasn’t just a challenge to see if Nguyen has the physical strength to hold down an 80-pound animal, but instead to learn about a capture method that researchers in Vietnam and Laos might be able to use to catch Large-antlered Muntjac for a conservation breeding program to save the species.

Protecting Vietnam’s Ungulate Species

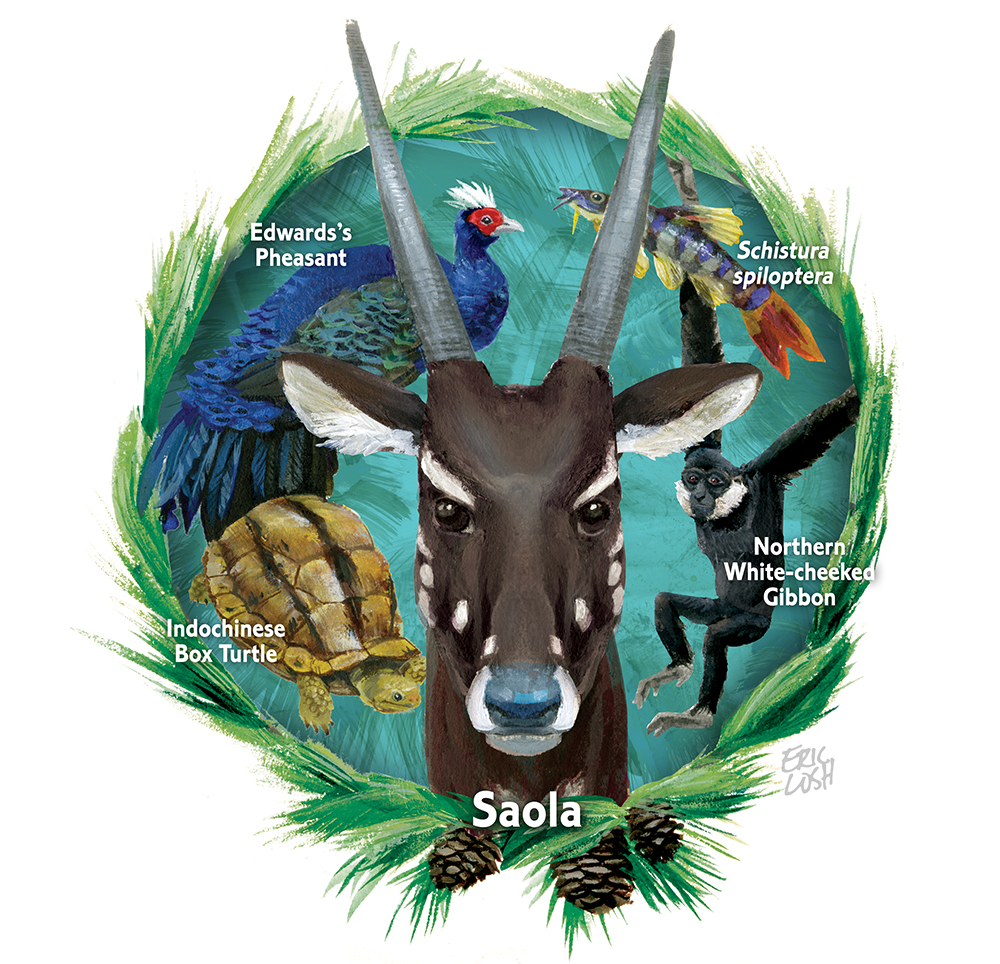

Large-Antlered Muntjac and Saola are among the rarest and most threatened large mammal species globally. Endemic to the Annamite Mountains of Vietnam, the IUCN Red List currently categorizes both Large-Antlered Muntjac and Saola as Critically Endangered. Both species are victims of the widespread and illegal use of hunting snares. Use of snares in Southeast Asian tropical forests is clearing these landscapes of their terrestrial wildlife species, leading to a phenomenon known as “empty forest syndrome.”

“Less than 25 years after its remarkable discovery, the Large-antlered Muntjac—like the Saola—is on the verge of extinction,” said Andrew Tilker, leader of the SWG’s Large-antlered Muntjac Task Team. “We can’t let this remarkable species follow in the footsteps of the Kouprey or Schomburgk’s deer—two other Southeast Asian ungulates that have slipped into extinction. We must secure a captive breeding population for the species. And with such a great group of team members dedicated to this project, I know we will succeed.”

For both species, the best hope for survival is a conservation breeding program, which requires bringing the animals from the wild into the center, caring for them to high international standards, and breeding them successfully. The SWG in partnership with the governments of Vietnam and Laos, aim to first attempt this with Large-antlered Muntjac, then Saola.

A rare camera-trap image of a Large-antlered Muntjac in Lang Biang Biosphere Reserve in south-central Vietnam. (Photo credit: The Southern Institute of Ecology, Saola Working Group, Global Wildlife Conservation and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research)

“There are currently no monitored wild populations or captive populations of Large-antlered Muntjac or Saola,” Nguyen says. “We don’t want these species to go the way of the Javan Rhino in Vietnam, with no chance to recover their populations. But if we do save these species, it will be such an inspiring national story of wildlife conservation in Vietnam and will inspire the public to learn more about conservation issues.”

Before the conservation breeding program can start, SWG researchers need to find a safe and effective method of capturing Large-Antlered Muntjacs in the wild

For some hands-on experience and a firsthand look, in January Nguyen flrew from Vietnam to Idaho to work with Mark Hurley, the wildlife research supervisor of the Idaho Fish and Game Department, where she learned to capture and collect information on wild Mule Deer. Nguyen’s professor, Mark Hebblewhite at the University of Montana, first suggested that she make the trek and helped arranged the trip.

The Art of Drive Netting

One of the methods that Hurley and the Idaho Fish and Game Department use to capture and collect biological information on Mule Deer in the wild is a combination of drive netting and GPS collar tracking. This capture method uses helicopters to drive individuals of the target species short distances into nets set up at the bottom of draws or in tall vegetation, while researchers hide nearby.

Once the Mule Deer (usually a yearling or adult doe) becomes entangled in the net, the research team gently but firmly holds it down to prevent injury to both the animal and researchers. Then a team member attaches a GPS collar, which helps researchers determine where Mule Deer migrate, how they use their habitat and their mortality rate. This isn’t such an easy task for everyone, says Nguyen, who weighs in at only 114 pounds, but had to help restrain animals that weighed between 70 and 100 pounds. The team releases the deer back into the wild after collecting information to determine the animal’s age, body weight and length of the hind leg.

“Helicopter drive netting is the safest way to capture deer, even though it can occasionally be hard on the capture staff,” writes Jim Lukens, the regional supervisor for the Salmon Region in Idaho, in a press release. “Mortality of deer captured in drive nets is the lowest of any other capture method used for mammals…this is an efficient and essential tool for the management of our herds.”

Using drive nets, Nguyen, Hurley and their large team handled up to 20 animals a day. However, while drive net techniques have proven successful at capturing Mule Deer, Nguyen says she’s not sure yet that it’s the best fit for capturing Large-antlered Muntjac in the denser forests of Laos and Vietnam.

Although SWG may not ultimately use Idaho’s drive net technique in its Annamite ungulate conservation programs, Nguyen says she believes her experience with Mule Deer in Idaho provides a strong foundation for her research on Large-Antlered Muntjac.

“I am so grateful to the SWG, Professor Hebblewhite and Mark Hurley for providing this opportunity,” Nguyen says. “This experience gave me some insight into setting up a drive net, which factors make this successful, how to handle animals once they become trapped in the nets, how many people are needed on the research team, and how to safely handle captured animals. Even if we can’t use this exact method on Large-antlered Muntjac, it was great for me to get some experience in handling these animals safely and seeing what works in this habitat.”

Nguyen says that ultimately SWG may need to use a variety of capture methods to catch Large-antlered Muntjac and the team will need to practice to perfect its methodology. In the end, her trip to Idaho has helped put her one step closer to protecting the ungulates she loves.

“Sometimes it’s hard to stay hopeful, but as long as I keep doing everything I can to ensure the animals are protected, hope will come for both of us,” Nguyen says. “Just like I have to have hope that even though I haven’t gotten to see a Large-Antlered Muntjac in the wild yet, someday I will.”